By Dr. Rob Shimko

Commedia dell’arte is an original form of theatre that emerged in northern Italy during the Renaissance. The term “commedia dell’arte” literally translates to “play of professional artists.” This distinguished the style from amateur dramatics, as well as the commedia erudita (“academic” or “learned” comedy adapted directly from Ancient Roman works and performed for aristocratic audiences.)

Traditional Italian commedia companies usually consisted of ten performers, typically seven men and three women (though some companies had as few as eight performers total and others as many as twelve). Commedia troupes were often organized by individual families, with the company members all being related to one another. The troupes were often itinerant, traveling from town to town in a manner that was first seen 1,500 years earlier in the Hellenistic period, when Greek and Roman theatre groups called mimes toured around the northern Mediterranean region. Renaissance Italian commedia companies performed in a variety of spaces, ranging from town squares and outdoor theatres to the homes of wealthy merchants as and royal courts. Although they sometimes staged more serious works, the Renaissance Italian commedia dell’arte troupes were known mostly for comedies.

The prototypical commedia plot features a pair of young lovers who are kept apart by the miserliness and/or lecherousness of their older male relatives. They receive aid from clever servants and eventually their love wins out. This fundamental plot structure has its roots in the ancient Roman comedies of Plautus and Terrence, though commedia dell’arte incorporated a number of unique new aspects to the history of European comedy. Commedia dell’arte was hugely popular both in Italy and in neighboring France, and its plots and stock character types can be seen in theatrical comedies from across Europe in the succeeding centuries. There are even records of commedia dell’arte troupes performing in such far-flung locales as Stockholm and Moscow.

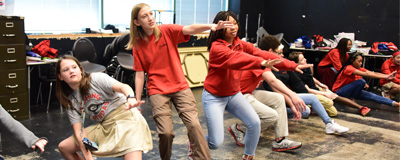

One of the defining features of commedia dell’arte during its heyday from roughly 1550-1750 A.D. was that the actors improvised much of the dialogue based on scenarios that provided a plot outline, but little more. The actors would thus make up the lines and moment-to-moment actions as they went along. Over 1,000 short commedia scenarios survive from this period, giving us a glimpse into the working method of the masterful improvisers who fleshed out these plots live in front of their audiences.

One of the things that made improvised commedia acting a bit more manageable for the performers was that they frequently played the same stock character types for much of their careers. These character types included Pantalone, a miserly and sometimes lecherous old Venetian man; Dottore, a foolish Latin-quoting pedant overly concerned with his neighbors’ affairs; the cowardly braggart soldier called Capitano; and a number of comic servants called zanni, who were sometimes slyly clever and other times laughably foolish. The most famous of the comedic servants was Arlecchino (also known as Harlequin) who was known for his colorful patchwork jacket. The clever and lighthearted Arlecchino would often undermine the plans of his master while pursuing his own pleasures, including eating as well as he could and seeking love with the outspoken and pragmatic female servant Columbina. Commedia scenarios also typically featured a pair of young lovers–the innamorato (male) and the innamorata (female)–usually played a bit more seriously than the more caricatured servants and old men, whose desire to be married is blocked by the shenanigans of Pantalone and Dottore. Actors who specialized in playing the lovers often memorized volumes of love poetry to pepper throughout their improvised dialogue. The innamorati sometimes borrowed passages from the more formal commedia erudita style.

Also part of the commedia actor’s bag of tricks were standard entrance and exit speeches that could be repeated from performance to performance. Prepared jokes and musical duets were also employed regularly. The most famous baseline technique for commedia performers was the use of lazzi (singular lazzo)–standard bits of comic business that they would return to time and again. One example is the Lazzo of the Straw, in which a higher status character would pour wine for himself, only to have his glass drained by a servant using a straw. An example of a solo lazzo involved Capitano becoming entangled with his sword so that it ended up between his legs as a mocking phallic symbol. The Lazzo of Nightfall involved the entire cast onstage stumbling around as if the space were pitch black. With the exception of the young lovers, commedia characters were typically masked, with the distinctive features of each mask speaking to the qualities of each archetypal character and making them immediately identifiable to the audience.