The Sound before the Silence

by Andy Knight, South Coast Repertory

In 1953, after 90 years as a French protectorate, Cambodia won its independence. The Southeast Asian country was now the Kingdom of Cambodia. In 1955, general elections were held. Prince Norodom Sihanouk, who had abdicated as king in pursuit of a political career, and his newly established party, Sangkum Reastr Niyum (People’s Socialist Community), triumphed: the Sangkum party won every seat in Parliament, and the Prince was appointed prime minister. The Sihanouk era had begun.

The Prince envisioned postcolonial Cambodia as a modern nation. He sought to improve the country’s infrastructure and to foster a strong national identity (which often meant harsh punishment for far-left dissidents). To Sihanouk, modernity also required cultural relevance, and the arts and entertainment boomed in Cambodia during the 1950s and ’60s. But the country’s music enjoyed a particular renaissance—for it was during this era that rock and roll came to Cambodia.

Even before the arrival of rock and roll, Cambodia’s popular music had incorporated foreign influences. While the country was still a protectorate, folk musicians integrated Western instruments into their ensembles and Latin beats into their songs. By the 1960s, the youth in urban Cambodia were hooked on yé-yé music, French pop named after the common refrain “yeah, yeah.” Then, as the United States’ military presence in neighboring Vietnam increased, English-language rock and roll became popular.

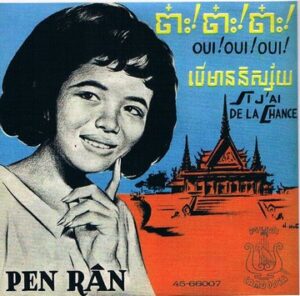

Throughout the 1960s and early ’70s, Cambodian musicians recorded Khmer-language covers of foreign songs. But as a whole, Cambodia’s rock was far more than a mere imitation of a Western form. Artists composed and recorded original songs that addressed national concerns and challenged contemporary attitudes; and both covers and original pieces combined Western-inspired melodies with a distinctly Cambodian sound. The music’s unique identity was also embodied in its greatest stars. Singers such as Ros Serey Sothea and Sinn Sisamouth appealed to a wide audience with a modern sound that was complemented by traditional looks and performance styles. Other artists, such as Pan Ron and Liv Tek, epitomized the term “rock star” with their unrestrained, raucous performances.

By 1969, Cambodia was on the brink of a new political era. While Sihanouk ruthlessly contended with the country’s far-left communist revolutionaries—whom he nicknamed the Khmer Rouge—he lost the support of urban Cambodians, who disapproved of his government’s corruption. Finally, in March 1970, while Sihanouk was in France, General Lon Nol and Prince Sisowath Sirik Matak, both high-ranking government officials, orchestrated a coup with the unspoken permission of the United States. The Kingdom of Cambodia was now the Khmer Republic.

During the five years that followed, Cambodia was enmeshed in a civil war as the U.S.-backed Lon Nol government fought the tenacious Khmer Rouge. But in Phnom Penh, Cambodia’s capital, the music persevered. The sounds of rock and roll would not be quieted—not by the U.S. bombs dropped on eastern Cambodia in the name of the Vietnam War, nor the rampant corruption within Lon Nol’s government, nor the growing number of Khmer Rouge guerilla fighters.

Then, on April 17, 1975, the Khmer Rouge breached Phnom Penh, and the music finally stopped. The war was over, and the victors swiftly instituted their vision for a new society. Over the next four years, approximately two million Cambodians would be exterminated by the Khmer Rouge, including ninety percent of the country’s musicians.

But miraculously, many of their recordings survived.

Article used with permission from South Coast Repertory.